If you search for “transition” on Google, it actually gives a specific definition for gender transition: to “adopt permanently the outward or physical characteristics of the gender one identifies with, as opposed to those associated with one’s birth sex.” It’s an incomplete definition, of course: it’s not just outward characteristics that change. Neither are they always the most important changes which that assume such changes happen at all: being transgender doesn’t always mean having extreme discomfort with the body you’re born with, as we’ll talk about later. But transitioning, in whatever form it takes, does mean a change that radically alters an individual. Many transgender people, very appropriately, refer to this as a “journey”.

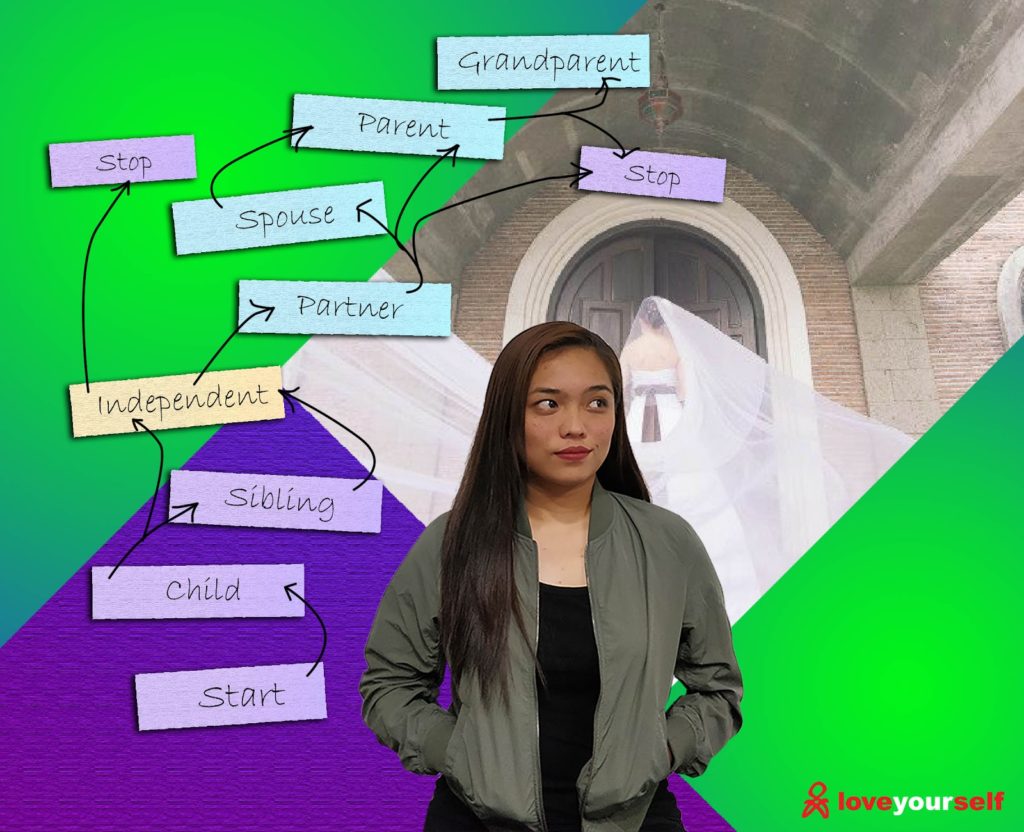

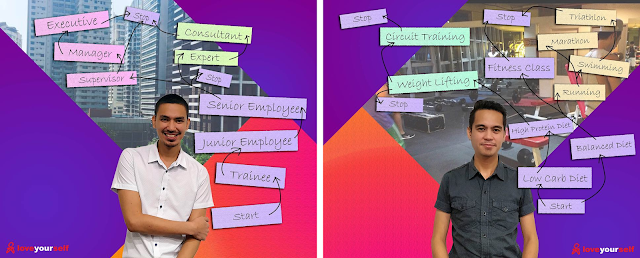

While we are talking about transgender people specifically, it’s helpful to note that every person “transitions” at many points in their lives. We transition when we grow up and take on new responsibilities. We transition when we leave a place or a profession. We transition with every joy and tragedy, like the birth of a child or the death of a parent. Other transitions take place subtly over long periods of time, like when a person acclimates to living in another country. All of these transitions take place in different contexts, and while there are definitely patterns in the stories people tell, each person brings their own memories and imaginations into them. There is no single way of transitioning in any way for any person, so the possibilities are as endless as our capacities to imagine them. Think about your own transition from grade school to high school, and see just how different these experiences can be between you and your classmates. You may not have even transitioned to high school at all, and your life may have moved in a different direction.

For many transgender people, these periods of transition are numerous, with many goal posts, successes, disappointments, beginnings, and endings. I invite you to ask your own transgender friends and see what stories they have to share.

Types of Transitioning for Transgender People

In medical, psychological, and rights-based language, you find a distinction between “medical” transitioning and “social” transitioning. The history of this distinction is interesting in itself and some aspects of one can very well overlap with another. Medical transitions refer mainly to changes to one’s physiological makeup. This includes changes things such as the endocrine system (e.g. hormone replacement therapy) or to one’s physical sex characteristics (e.g. gender-affirmation surgery or also referred to as sex reassignment surgery). Many transgender people strongly believe that being able to change one’s body is important so it matches how they see themselves in their hearts and minds. (If you think about it, this is precisely what a lot of people who beef up at the gym do. The only difference is that people who work on their fitness are seen as culturally appropriate.) But just as many don’t feel that way. One person’s journey might involve extreme discomfort with their bodies, brought about perhaps by their society’s obsession with the physical body and its obsessive stereotyping of people based on what they think genders can or cannot be. Another journey might not have such discomforts, and the struggle could be elsewhere. Both journeys are equally true and meaningful.

Social transitions on the other hand refer to changes in a person’s social, cultural, and political life. These don’t necessarily require medical intervention. This includes many of the things we are familiar with, like dress, behavior, and ways of relating to others. On the transgender person’s side of things, this can include wearing the clothes that match the gender they identify as, coming out as transgender to friends and family, and adopting habits that we might associate with their identified gender. On the side of those around them this might include using the pronoun they ask us to, referring to them by the name they adopt for themselves, and other things. The point here being that transitioning is about aligning their inner experience of gender and their outward expressions, and that those around them are also part of this process.

Responding to transitioning affirmatively

In the Philippines, as in many places here in Southeast Asia, the transitioning process of a transgender person appears to go against many long-standing cultural values. People believe that gender can only ever be lalaki or babae; that a person is born into these roles by virtue of their reproductive organs; and that these are unchanging facts of biology, history, and morality. Historically, this was not always the case, and there many reasons for this. But what’s important is that these beliefs have consequences. In this case, the consequence is that we are left unequipped for such transitions. Our cultures has many tools for, say, a death of a parent: the wake, the funeral, the various types of behaviors recognized as grieving, the general understanding that you need time to deal with this strange experience, and so on. It is only in the past few decades that we have started imagining and creating such cultural tools for those transitioning from the gender they were assigned at birth to the gender of their hearts.

The reference to death is not accidental. Many families I’ve had the opportunity to know do describe their experiences in these terms. They talk about the “death” of a person they once knew, the death of the boy or the girl they raised from birth, that sort of thing. As unnerving as it is, there’s a good reason “death” is the word they use. When we listen more closely, they are not expressing not violent horror or malicious rejection (though this is definitely the case for others and we cannot ignore that suffering); they are expressing confusion and pain, both misplaced and misunderstood, and a genuine desire for the love to push through. In the average person I meet, it is ignorance and not blatant transphobia that makes them do sad, hurtful, and stupid things. But certainly we can avoid a lot of the sad, hurtful, and stupid behavior altogether.

In the case of transitioning, part of making our culture more affirming to the transgender person’s experience is by changing this core mindset. Death need not be terrifying or negative. In funerals, we often have storytelling and eulogies of the beautiful life who has left us, and we have songs and silent contemplation about how that beautiful life can teach us so our own lives in the present can be beautiful too. They can and should be celebrations. And what I often say to the families I’ve met is that nobody has actually died: their brother and sister, their son or daughter, is still there, and there is a new phase of life that has the potential to be full of beauty if we allow it. We don’t need to think by ourselves how a person’s life can enrich our own; that person is there waiting to live life with you.

The fist point I’d like to make here is not for the transgender person, but for the people around them. This is difficult, but the first thing we all need to do is to stop all the moralizing and gut responses of anger and disgust. All that talk of immorality or unnatural is both scientifically and logically incoherent. But the worst part is that all that talk keeps us from recognizing the real issue: that this experience of having a friend or family member who is transitioning does not make sense and it is deeply troubling to you. And if you look closer, you may also discover that you are troubled because something is getting in the way of your love. Put simply, it would not be so distressing or confusing if you did not care. But you do care. You love them, and that love shines bright and true through the haze of that confusion. But you don’t know this person anymore. In a sense, this is true: the person you imagined you friend or family member would be, is not who you expected or perhaps wanted to be. So who do you love now? And how do you love them?

Some recommendations from love

The question of how to love emphasizes the point that transitioning, especially in the context of the average family, is not a one-sided affair. Everyone needs to transition. While it’s not always the case, some may need grief or some other emotion to deal with the shock. But when the dust has settled, everyone needs to get to know all over again their transgender child, or uncle or aunt, or brother or sister. It’s not kuya anymore, but ate. It’s not Jason anymore, but Janice. It’s she, not he. There may no longer be marriage or grandchildren, or maybe there will be, but that’s another story altogether. The words and names you grew up with are no longer appropriate in the light of new circumstances, and that can be deeply disturbing to many. Again, who do you love now? How do you love them? Progress is when we start asking these questions frankly and openly.

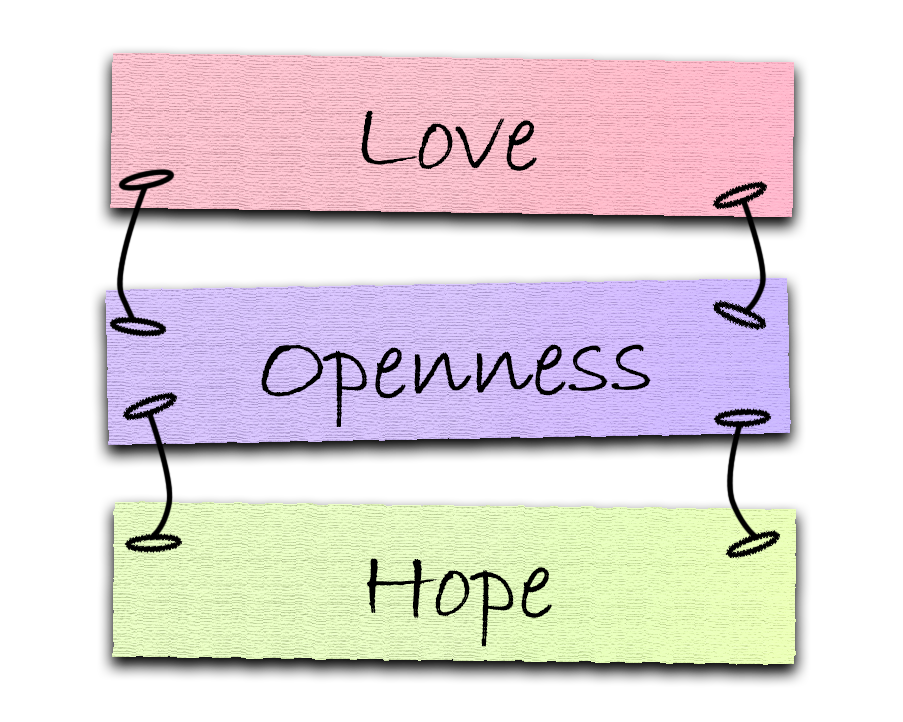

Love demands a lot of things. But perhaps the most relevant are patience, openness, and hope. This is good advice for both the transgender person and everyone around them. When we say patience, we acknowledge that this is going to take time. You need to get to know your transgender friend or family member, and getting to know them means recalibrating that sense of the world that has taken you your entire life to put together. This may or may not be a lot of hard work depending on where you’re coming from, but it is going to be work regardless. Something has to replace your old sense of the world. For the transgender person, this may include uncomfortable questions about whether someone is worth the hassle. Bridges may be mended or burned, as in any other kind of transition in life. Those are the options our present reality, with all its prejudices, has given us. But with imagination, these painful decisions can be a good thing. “When I transitioned, I found out who my real friends and family were” is a very common sentiment I hear from transgender people. And it’s a sentiment borne of an imagination that makes growth possible amidst truly unpleasant and even terrifying experiences.

As for openness, it’s not just about openness to new information; it’s about openness to experiences you’d rather not have, and to appreciate them as painful but necessary goalposts to your development as both a person and as a component of the family or friendship network you belong to. You are confused, and maybe even angry, because your son is now your daughter. Of course you are. Who wouldn’t be? But you’re not confused or angry because your child is transgender: you are confused and angry because so many of your dreams, desires, and expectations of your child are now moot. And you are confused and angry, most of all, because you are not sure how best to love your child anymore. Patience requires that we go through the motions of recalibrating all those dreams, desires, and expectations, but openness requires that we be open to the possibility that this has to happen. If we do not, then we remain stuck in confusion and anger because the roots of these emotions are not being allowed to change. The same is as true for the transgender child as it is for the parent: your own dreams, desires, and expectations about your relationship with your parents may need to change. This may or may not be pleasant, but you need to be open to it regardless.

Finally, there’s hope. You don’t just work through a thing and be open to whatever that thing throws at you: you look forward to something in return. You, your family, your friends – everybody involved needs to be committed to a vision of a future that sees everyone flourishing. It’s not an uncommon idea: all of medical science, all of psychology, and all of humans is built on the fundamental assumption that our work will help humankind flourish. Such that whatever the journey transgender people have, whatever the transition process might entail, everyone comes out better and stronger human beings.

For more resources on social transitioning, you may visit Victoria by LoveYourself (VLY) in Pasay City.

Text by Jan Gabriel M. Castañeda

Art by Franco Honesto Lasay & Mark de Castro