The HIV crisis has gone on for four decades, and for four decades the world has struggled against it. Doctors, scientists, educators, policy makers, writers, artists — people of all walks and all colors have, in their own ways, sought to make sense of this crisis and its relationship with society. From citizens to states, from medicine to prayer, from cures to cries for reform, people’s visions of how to respond to the crisis are as diverse as the people who bear its scars. The goal of this series is to give you a glimpse of these visions: the roles people of different passions and disciplines have played in this crisis that, as of March 2016 as recorded by the Department of Health’s Epidemiology Bureau, is infecting 25 Filipinos daily

In the poverty-ridden corners of India’s Ganjam district, a man is robbed by his own brothers; when the man turns to authorities for help, they turn on him instead and “beat him up until he vomited blood.” At another district, in Gonda, the unconscious bodies of a couple and their child are dragged to a nearby field and promptly set on fire (The suspects, relatives of the father, claimed it was a suicide.) During a raid at a small office in in Kyrgyzstan, a not uncommon occurrence among non-government organizations, police forces “threatened to rape all the people inside”3. And in clinics across Swaziland, near the eastern coast of Sub-Saharan Africa, people are driven off “like small devils”4 – some driven further off, into suicide. The eulogies grow ever numerous.

To any Christian, these stories do not simply horrify: these monstrous footnotes of world history draw from a deeper well of terror, so reminiscent of the history of their own faith. Suffering was rooted as firmly as their trust in God’s love: the martyrs knew blood, fire, and rape very well, and these traumas in Christianity’s infancy established a bond between faith and pain that has endured for two thousand years. They were marked in blood with the sign of the cross, for all the world to see.

But the martyrs of Ganjam, Gonda, Kyrgyzstan, and Swaziland were marked for a wholly different reason. Their bodies were laid to rest not with the sign of the cross, but with the bloody ink of a medical certificate. Three terrible letters.

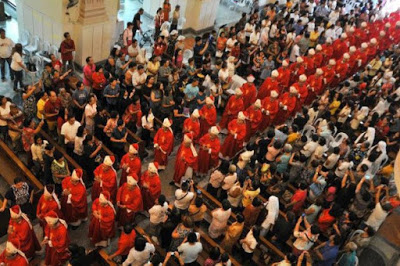

The Virus and the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines

Despite the counterintuitive claim of psychologist Steven Pinker that violence is declining globally5, the violence inflicted on those living with HIV prompt quite the opposite conclusion. (For women6 and LGBT people7 living with HIV, the pain is more pronounced, for not even violence is made equal in the eyes of God.) “The AIDS pandemic recreates for us the frightening world of the earlier church,” wrote African theologian Tinyiko Maluleke8, the lives of the early martyrs mirrored in those lives branded by three terrible letters. But our judging gaze need not look far. After all, in our own country, the wicked marriage of conservative religiosity and outdated public health policies9 had given birth to conditions that allow people to die young10 from an untreated virus. We are shocked: gone too soon, we say. But with all our lip service to them, we continue to be shocked by the idea of minors getting tested – that it is somehow too soon11 – even as conservative estimates place the number of adolescents living with HIV at nearly ten thousand12. Like some of the martyrs of the early church, they were hardly adults when they first knew suffering.

But the response of the Roman Catholic Church to this suffering, as embodied by the Catholic Bishop’s Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), has been something of a mess. To be fair, their assertion that families “be nuclei of care”13 is important: without a doubt, families have an important role to play14,15,16, and we need to include them in our HIV/AIDS programs. Their call for “deepening the spirituality of caring for people living and affected by HIV”17 is also without fault, as studies have already demonstrated faith’s potential in caring for those affected18,19. And in the CBCP’s HIV/AIDS primer20, they were absolutely right in writing that “structural injustice” was one of the roots of the epidemic. As medical anthropologist Paul E. Farmer and colleagues write: “HIV attacks the immune system in only one way, but its course and outcome are shaped by social forces having little to do with the universal pathophysiology of the disease”21.

In principle, the church’s position that “we have to welcome people living with HIV into our homes and into our parishes”22 makes perfect sense. Isolation and abandonment, in all its forms, are what fundamentally drive the epidemic. By standing together, as the early martyrs did, so much could be done. On these points, the research agrees wholeheartedly23,24,25. The light of truth prevails.

But that is where the light ends and the mess begins. One particularly messy statement, released in 201126, misrepresented the condom use promotion strategy of public health advocacies and wrongly interprets published research in favor of abstinence-only policies – policies which we know don’t work26,27,28,29,30,31. (As proof, consider that the Philippines currently holds the world records for highest rates of HIV infection32 and teenage pregnancy33.) A claim made in 201534 that most people living with HIV came from “broken families” is equally confusing. While a case should be made that dysfunctional social systems worsen the impact of HIV/AIDS on communities35,36,37,38, the term “broken family” is uselessly vague at best, obsessing over individual families rather than on focusing on larger social issues. And the claim that condom use was “tantamount to condoning promiscuity and sexual permissiveness” and helps spread the virus is not only dangerously moralistic: the best evidence tells us it is simply wrong39. This claim was made in the CBCP’s 1993 pastoral letter on HIV/AIDS40, but has not changed since then.

Overall, the CBCP’s official position has been deeply problematic. But most heartbreaking has been its impact on human lives. The opening message of the CBCP’s HIV/AIDS primer reads that “perfect love triumphs over stigma, and spreads joy, hope and salvation”, but this perfect love has been gruesomely mistranslated: it has entrenched stigma and buried us in a torrent of pseudoscience and misplaced guilt. And that despite their undoubtedly good intentions, the decades-old confession of the World Council of Churches that Christians “share responsibility for the fear that has swept our world more quickly than the virus itself”41 remains a confession whose penance remains unserved. “The great Christian themes of the goodness of creation, love and life,” theologian Paula Clifford laments, “appear to have been thrown into disarray”42. And this disarray, as far as the anecdotal evidence tells us, has only pushed Filipinos living with HIV away. Love’s only triumph here was that it successfully branded them as little devils.

Alternative Christian perspectives

Regardless of the ambitious etymology of the word “Catholic”, an old word meaning “universal” and “all-embracing”, the CBCP’s position is far from universal. For instance, in a recent statement of the Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research endorsed by internationally renowned theologians set the case bluntly: “official teachings on marriage and sexuality, based as they are on abstract notions of natural law and outdated, or at the very least scientifically uninformed, concepts of human sexuality are for the most part incomprehensible to the majority of the faithful”43. These teachings, which have made sexuality “incomprehensible” to many Christians, have also made it “unspeakable”: for the Christian Conference of Asia, it had created cultures which “inhibit open and honest discussion of human sexuality”44. The judgment of the Catholic Bishops of Myanmar was much more specific though, writing that “priests or bishops have stopped lay people from raising awareness about HIV … and even preventing them from giving scientifically proven sexual health information”45.

And in India, which bears the grief of Ganjam and Gonda, their conference of Catholic bishops offered a stern reminder: “Those who feel morally superior to those living with HIV/AIDS may remember that self-righteousness is condemned more than any other sin by Jesus in the pages of the Gospel”46. It was self-righteousness, after all, which drove people to burn an entire family alive.

This “spectacular theological error of the church”, in Paula Clifford’s words, has cultivated the toxic idea that “sexuality is nature’s strongest competitor for their loyalty to Christ”47. But it is not a universal feature of Christian thinking: in fact, there is a rich history of spiritual writing that is affirmative, rather than suspicious, of sexuality48,49,50,51. “It should not be too much to hope,” Professor Traci West writes, “for a space in the church where such concerns could be openly addressed as part of a broader understanding of Christian theology and human spirituality”52. And it is not too much: in fact, it is absolutely necessary. In Dr. Joseph Go words, “there is nothing human that is untouched by gender and sexuality”53 – and if theology is the study of God at work in human life, surely God must also be at work somewhere in sexuality, the HIV/AIDS crisis in particular. And we must find God quickly.

“For years the church has warned against the evil of sexual immorality,” reflects Pastor Arnau van Wyngaard of Swaziland, who tends to his flock in the country with the highest HIV prevalence in the world54. “But perhaps too little has been done to enable Christians to celebrate the gift of human sexuality that God has given to us”55. Too little, but hopefully not too late. More is being done to bridge this conversation of faith in addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and many have taken up the cross in the name of progress – not as a rod to strike the branded, but as a shepherd’s staff to lead and embrace them. “People Living with HIV-AIDS are like lepers of olden times who suffered from marginalization, stigmatization and alienation,” declares a 2011 statement by National Council of Churches in the Philippines, echoing a growing sentiment among the Christian faithful in the country that something has gone amiss and must be corrected by a fuller appreciation of the Christian vision of perfect love. “For we are alienated from ourselves and we lose that compassion to be caring for the least of Christ’s brothers and sisters who are created in the image of God”56.

Much more can be said, but it is sufficient to say that in order to fulfill the Christian faith’s proper role in addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic – in order for perfect love to really triumph – its churches must stop making martyrs out of its people. It must do more to wash off the bloody brand of those three terrible letters, and must look beyond the comfort of its conventions to do so. Borrowing the words of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines, the HIV/AIDS epidemic requires bringing to all “the gift of God’s grace that heals and accepts unconditionally”58. So that praises, not eulogies, may grow ever numerous.

Text by Jan Gabriel Castañeda

Photos from Photos taken from Catholic Bishops of the Philippines (CBCP) webpage,Hufftington Post, and Outsmart Magazine